[avatar user=”madison” size=”thumbnail” align=”left” link=”http://blog.blueventures.org/author/madison/” target=”_blank” /] by Madison Kane, Expedition Manager, Madagascar

Blue Ventures’ expeditions, is by no means just focused on diving. Though dive training and surveying plays a large part in expeditions life, there are many opportunities for volunteers to immerse themselves in Malagasy culture and work alongside our other conservation programmes.

Pitching our ‘tents’

Working within the Velondriake locally managed marine area (LMMA) means that we, Blue Ventures (BV), are trying to reach over 30 communities; spanning about 50 km of rugged coastline. In an area where as much as 87% of the population are completely reliant on marine resources, our community based aquaculture programme plays a critical role in diversifying livelihoods and providing alternative income sources to fishing. Although active in Velondriake for some time now, sea cucumber farming in the north of the LMMA has only recently come to completion. Consequently we, the expeditions team and volunteers, were extremely excited to be heading up there for the weekend to help out with the second ever sale of sea cucumbers in the small, remote village of Ambolimoke, 13 km north of our base camp Andavadoaka. As this was the first expedition to descend on this village, the occasion provided a perfect opportunity to plan some other activities, working across programmes to engage multiple communities.

Our trip began at sunrise on a fresh Friday morning, and we set out in four traditional sailing pirogues to Ambolimoke. The phrase ‘Arakarake Tsioke’ employed regularly by the Vezo, translating directly to ‘it depends on the wind’, was particularly apt in the crystal calm conditions that ensued!

On arrival in Ambolimoke five hours later, we were greeted with an unexpected, amazing brunch, which we inhaled whilst learning about the sea cucumber farming project from the aquaculture team who skilfully fielded all our questions. Rejuvenated, we set up camp, draping pirogue sails on the sand as a base sheet, and engineering stakes to hang our mosquito nets.

Twister anyone?

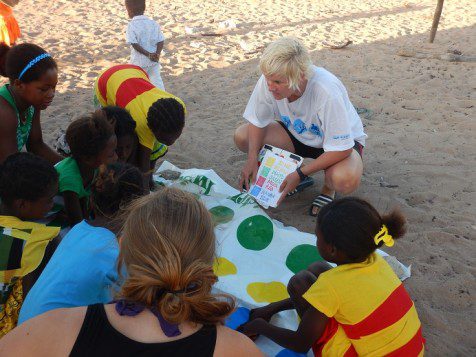

With energy still high, the volunteers were ready for action. Twenty paces from our camp we found the local school, consisting of one very small ‘vondro’ (thatch) hut, we greeted the wide variety of age ranges that had turned up from the village to learn a bit of English – an activity we had organised in advance. From our experiences teaching English three times a week in Andavadoaka, volunteers knew that interactivity was key, and had come prepared. We split the children into three groups adults, teenagers and younger children. One group started learning the alphabet song, whilst a highly energetic game of ‘Duck-Duck-GOOSE’ or should I say, ‘Goat-Goat-BENGY’, was played outside to teach animal names to the second. Finally colours and body parts were taught through the medium of Twister to the third. The sessions were a raging success and everyone asked for more!

We regrouped at the camp, under the setting sun, feeling satisfied that we had made a positive impact and awestruck at how passionately the village wanted to learn English. After rustling around for our torches, we were all then ushered in pairs to various houses in the village who warmly welcomed us in to share a meal with them. These families were also sea cucumber farmers and we would meet them again later to help with their harvests.

Getting up close and personal with sea cucumbers

Due to the nature of the sea cucumber species (Holothuria Scabra) farmed in Ambolimoke, , which burrows into the sand during the day, harvesting can only take place at night during a low spring tide. So at 10pm after an inadequate nap, we donned booties and torches , and were shocked awake by the cold water. We tentatively waded out into the dark moonlit sea for the night harvest, navigating the treacherous underwater terrain with care, for fear of falling in. Once at the pens, we were reunited with the farmers from our homestays and began gathering all the sea cucumbers we could find. Only those over 400g made the cut, with the rest returned to their pens to continue growing. The expertise of the aquaculture technicians was impressive, as they navigated the large piles of potential sea cucumber candidates for sale with ease, often not needing to weigh them to know the outcome.

By about 1am, the collection was complete and after a short but much needed rest we woke with the sun to eviscerate (squeeze out the insides), clean, and prepare the harvested sea cucumbers – not an activity for weak stomachs! The sea cucumbers were then (as always) purchased by a company called Indian Ocean Trepang (IOT) and would be later sold internationally (mostly in Asia) where they are coveted for their medicinal and aphrodisiac qualities.

Snorkelling fun in Bevato

Sale complete, we capitalised on our early morning, trekking nearly 5 km to the next village, Bevato where the village president, Nahoda Marsily, and the president of the Velondriake Association, Samba Roger greeted us warmly, articulating their appreciation of us coming to visit their permanent reserve, of which they are very proud. ‘Take only photos and leave only bubbles’ were the rules, and with that in mind, we soared away on our pirogues to check out the area of barrier reef that Bevato designated as a permanent reserve in 2010. Despite less than ideal snorkelling conditions, our group of volunteers were very invested in this trip, eager to demonstrate the non-extractive value of conservation, and had a great time examining the area of protected reef with the guides ensuring safety and making sure the best spots were explored.

Getting to grips with English

Surfing back into Bevato through the barrier reef breakwater at speed, with sailors wailing racing cries was certainly a highlight that left us all exhilarated, ready to teach another session of English, arranged for after lunch. This time we organised a scavenger hunt, where in groups of about 15, we raced round the village finding objects to match to English words. Whilst determined children ran around trying to find the relevant objects (even octopus and mangroves), write their names in Malagasy and take photos with them, the adults of the village learnt basic greeting phrases, acting them out to each other whilst trying not to laugh.

To top the day off, a sunset walk back along the coast accompanied by half the village of Bevato, through the spiny and baobab forest was spectacular, and a satisfactory wave of fatigue swept over us all. Tired and ravenous by the time we arrived back to Ambolimoke, we settled down to a magnificent goat barbeque and bon fire with a bit of Ukulele thrown in for good measure.

BBQ, Madagascar style

Exhausted, yet happy, another night under the stars was magical (although a little chilly), and with the moon still high in the morning sky, we packed up camp and started for home. Though sad to leave after such a productive and fun trip, one volunteers later quoted ‘that it was one of the best parts of the expedition’ as they were happy to witness first-hand that ‘blue ventures project integration in the field is spectacular!’, I was also excited that this expedition had gone so well, with our volunteers so keen to get involved and make the most of the experience. Consequently, I know expeditions will be back soon to build on what we started, particularly as aquaculture and marine management in general continues to expand in these remote northern villages of Velondriake.